Vector Search Basics

If you are still trying to figure out how vector search works, please read ahead. This document describes how vector search is used, covers Qdrant’s place in the larger ecosystem, and outlines how you can use Qdrant to augment your existing projects.

For those who want to start writing code right away, visit our Complete Beginners tutorial to build a search engine in 5-15 minutes.

A Brief History of Search

Human memory is unreliable. Thus, as long as we have been trying to collect ‘knowledge’ in written form, we had to figure out how to search for relevant content without rereading the same books repeatedly. That’s why some brilliant minds introduced the inverted index. In the simplest form, it’s an appendix to a book, typically put at its end, with a list of the essential terms-and links to pages they occur at. Terms are put in alphabetical order. Back in the day, that was a manually crafted list requiring lots of effort to prepare. Once digitalization started, it became a lot easier, but still, we kept the same general principles. That worked, and still, it does.

If you are looking for a specific topic in a particular book, you can try to find a related phrase and quickly get to the correct page. Of course, assuming you know the proper term. If you don’t, you must try and fail several times or find somebody else to help you form the correct query.

A simplified version of the inverted index.

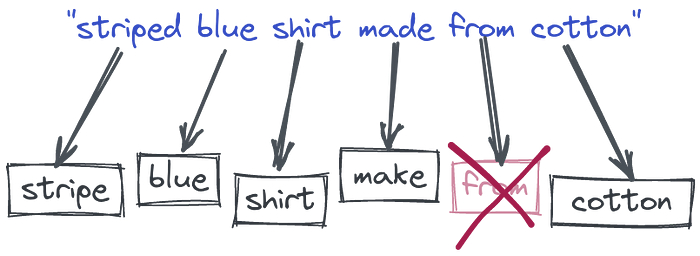

Time passed, and we haven’t had much change in that area for quite a long time. But our textual data collection started to grow at a greater pace. So we also started building up many processes around those inverted indexes. For example, we allowed our users to provide many words and started splitting them into pieces. That allowed finding some documents which do not necessarily contain all the query words, but possibly part of them. We also started converting words into their root forms to cover more cases, removing stopwords, etc. Effectively we were becoming more and more user-friendly. Still, the idea behind the whole process is derived from the most straightforward keyword-based search known since the Middle Ages, with some tweaks.

The process of tokenization with an additional stopwords removal and converstion to root form of a word.

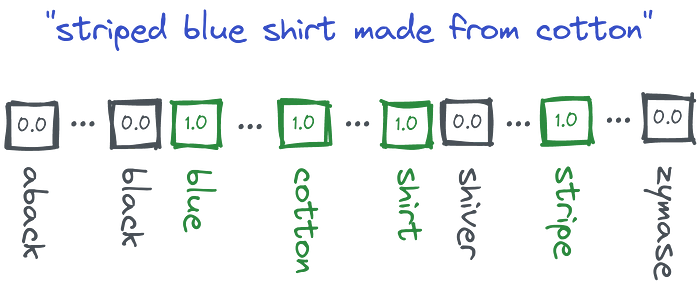

Technically speaking, we encode the documents and queries into so-called sparse vectors where each position has a corresponding word from the whole dictionary. If the input text contains a specific word, it gets a non-zero value at that position. But in reality, none of the texts will contain more than hundreds of different words. So the majority of vectors will have thousands of zeros and a few non-zero values. That’s why we call them sparse. And they might be already used to calculate some word-based similarity by finding the documents which have the biggest overlap.

An example of a query vectorized to sparse format.

Sparse vectors have relatively high dimensionality; equal to the size of the dictionary. And the dictionary is obtained automatically from the input data. So if we have a vector, we are able to partially reconstruct the words used in the text that created that vector.

The Tower of Babel

Every once in a while, when we discover new problems with inverted indexes, we come up with a new heuristic to tackle it, at least to some extent. Once we realized that people might describe the same concept with different words, we started building lists of synonyms to convert the query to a normalized form. But that won’t work for the cases we didn’t foresee. Still, we need to craft and maintain our dictionaries manually, so they can support the language that changes over time. Another difficult issue comes to light with multilingual scenarios. Old methods require setting up separate pipelines and keeping humans in the loop to maintain the quality.

The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel.

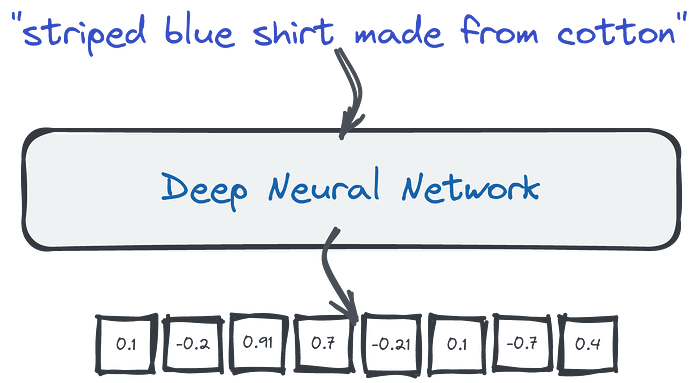

The Representation Revolution

The latest research in Machine Learning for NLP is heavily focused on training Deep Language Models. In this process, the neural network takes a large corpus of text as input and creates a mathematical representation of the words in the form of vectors. These vectors are created in such a way that words with similar meanings and occurring in similar contexts are grouped together and represented by similar vectors. And we can also take, for example, an average of all the word vectors to create the vector for a whole text (e.g query, sentence, or paragraph).

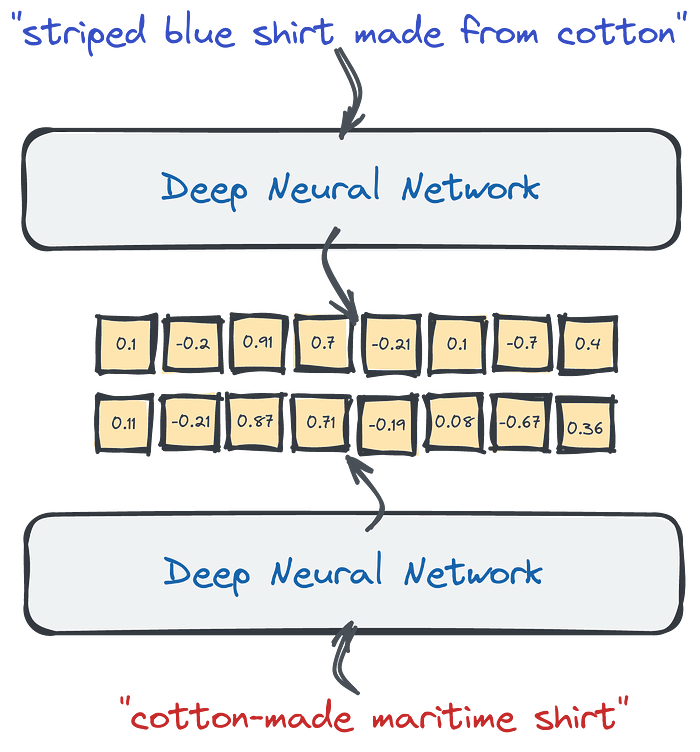

We can take those dense vectors produced by the network and use them as a different data representation. They are dense because neural networks will rarely produce zeros at any position. In contrary to sparse ones, they have a relatively low dimensionality — hundreds or a few thousand only. Unfortunately, if we want to have a look and understand the content of the document by looking at the vector it’s no longer possible. Dimensions are no longer representing the presence of specific words.

Dense vectors can capture the meaning, not the words used in a text. That being said, Large Language Models can automatically handle synonyms. Moreso, since those neural networks might have been trained with multilingual corpora, they translate the same sentence, written in different languages, to similar vector representations, also called embeddings. And we can compare them to find similar pieces of text by calculating the distance to other vectors in our database.

Input queries contain different words, but they are still converted into similar vector representations, because the neural encoder can capture the meaning of the sentences. That feature can capture synonyms but also different languages..

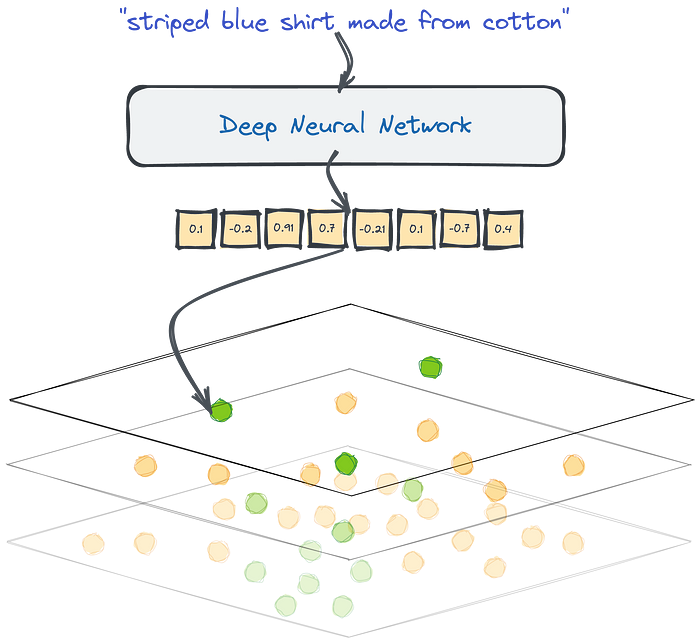

Vector search is a process of finding similar objects based on their embeddings similarity. The good thing is, you don’t have to design and train your neural network on your own. Many pre-trained models are available, either on HuggingFace or by using libraries like SentenceTransformers. If you, however, prefer not to get your hands dirty with neural models, you can also create the embeddings with SaaS tools, like co.embed API.

Why Qdrant?

The challenge with vector search arises when we need to find similar documents in a big set of objects. If we want to find the closest examples, the naive approach would require calculating the distance to every document. That might work with dozens or even hundreds of examples but may become a bottleneck if we have more than that. When we work with relational data, we set up database indexes to speed things up and avoid full table scans. And the same is true for vector search. Qdrant is a fully-fledged vector database that speeds up the search process by using a graph-like structure to find the closest objects in sublinear time. So you don’t calculate the distance to every object from the database, but some candidates only.

Vector search with Qdrant. Thanks to HNSW graph we are able to compare the distance to some of the objects from the database, not to all of them.

While doing a semantic search at scale, because this is what we sometimes call the vector search done on texts, we need a specialized tool to do it effectively — a tool like Qdrant.

Next Steps

Vector search is an exciting alternative to sparse methods. It solves the issues we had with the keyword-based search without needing to maintain lots of heuristics manually. It requires an additional component, a neural encoder, to convert text into vectors.

Tutorial 1 - Qdrant for Complete Beginners Despite its complicated background, vectors search is extraordinarily simple to set up. With Qdrant, you can have a search engine up-and-running in five minutes. Our Complete Beginners tutorial will show you how.

Tutorial 2 - Question and Answer System However, you can also choose SaaS tools to generate them and avoid building your model. Setting up a vector search project with Qdrant Cloud and Cohere co.embed API is fairly easy if you follow the Question and Answer system tutorial.

There is another exciting thing about vector search. You can search for any kind of data as long as there is a neural network that would vectorize your data type. Do you think about a reverse image search? That’s also possible with vector embeddings.