On Hybrid Search

Kacper Łukawski

·February 15, 2023

There is not a single definition of hybrid search. Actually, if we use more than one search algorithm, it might be described as some sort of hybrid. Some of the most popular definitions are:

- A combination of vector search with attribute filtering. We won’t dive much into details, as we like to call it just filtered vector search.

- Vector search with keyword-based search. This one is covered in this article.

- A mix of dense and sparse vectors. That strategy will be covered in the upcoming article.

Why do we still need keyword search?

A keyword-based search was the obvious choice for search engines in the past. It struggled with some common issues, but since we didn’t have any alternatives, we had to overcome them with additional preprocessing of the documents and queries. Vector search turned out to be a breakthrough, as it has some clear advantages in the following scenarios:

- 🌍 Multi-lingual & multi-modal search

- 🤔 For short texts with typos and ambiguous content-dependent meanings

- 👨🔬 Specialized domains with tuned encoder models

- 📄 Document-as-a-Query similarity search

It doesn’t mean we do not keyword search anymore. There are also some cases in which this kind of method might be useful:

- 🌐💭 Out-of-domain search. Words are just words, no matter what they mean. BM25 ranking represents the universal property of the natural language - less frequent words are more important, as they carry most of the meaning.

- ⌨️💨 Search-as-you-type, when there are only a few characters types in, and we cannot use vector search yet.

- 🎯🔍 Exact phrase matching when we want to find the occurrences of a specific term in the documents. That’s especially useful for names of the products, people, part numbers, etc.

Matching the tool to the task

There are various cases in which we need search capabilities and each of those cases will have some different requirements. Therefore, there is not just one strategy to rule them all, and some different tools may fit us better. Text search itself might be roughly divided into multiple specializations like:

- Web-scale search - documents retrieval

- Fast search-as-you-type

- Search over less-than-natural texts (logs, transactions, code, etc.)

Each of those scenarios has a specific tool, which performs better for that specific use case. If you already expose search capabilities, then you probably have one of them in your tech stack. And we can easily combine those tools with vector search to get the best of both worlds.

The fast search: A Fallback strategy

The easiest way to incorporate vector search into the existing stack is to treat it as some sort of fallback strategy. So whenever your keyword search struggle with finding proper results, you can run a semantic search to extend the results. That is especially important in cases like search-as-you-type in which a new query is fired every single time your user types the next character in. For such cases the speed of the search is crucial. Therefore, we can’t use vector search on every query. At the same time, the simple prefix search might have a bad recall.

In this case, a good strategy is to use vector search only when the keyword/prefix search returns none or just a small number of results. A good candidate for this is MeiliSearch. It uses custom ranking rules to provide results as fast as the user can type.

The pseudocode of such strategy may go as following:

async def search(query: str):

# Get fast results from MeiliSearch

keyword_search_result = search_meili(query)

# Check if there are enough results

# or if the results are good enough for given query

if are_results_enough(keyword_search_result, query):

return keyword_search

# Encoding takes time, but we get more results

vector_query = encode(query)

vector_result = search_qdrant(vector_query)

return vector_result

The precise search: The re-ranking strategy

In the case of document retrieval, we care more about the search result quality and time is not a huge constraint. There is a bunch of search engines that specialize in the full-text search we found interesting:

- Tantivy - a full-text indexing library written in Rust. Has a great performance and featureset.

- lnx - a young but promising project, utilizes Tanitvy as a backend.

- ZincSearch - a project written in Go, focused on minimal resource usage and high performance.

- Sonic - a project written in Rust, uses custom network communication protocol for fast communication between the client and the server.

All of those engines might be easily used in combination with the vector search offered by Qdrant. But the exact way how to combine the results of both algorithms to achieve the best search precision might be still unclear. So we need to understand how to do it effectively. We will be using reference datasets to benchmark the search quality.

Why not linear combination?

It’s often proposed to use full-text and vector search scores to form a linear combination formula to rerank the results. So it goes like this:

final_score = 0.7 * vector_score + 0.3 * full_text_score

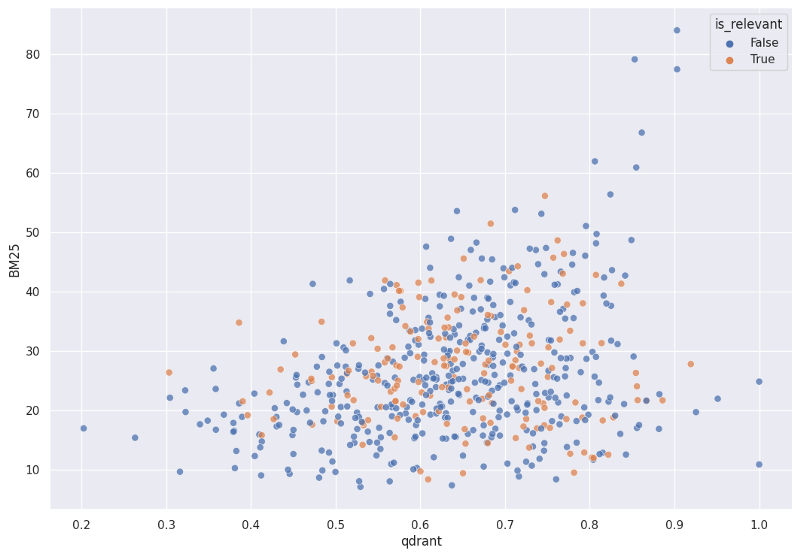

However, we didn’t even consider such a setup. Why? Those scores don’t make the problem linearly separable. We used BM25 score along with cosine vector similarity to use both of them as points coordinates in 2-dimensional space. The chart shows how those points are distributed:

A distribution of both Qdrant and BM25 scores mapped into 2D space. It clearly shows relevant and non-relevant objects are not linearly separable in that space, so using a linear combination of both scores won’t give us a proper hybrid search.

Both relevant and non-relevant items are mixed. None of the linear formulas would be able to distinguish between them. Thus, that’s not the way to solve it.

How to approach re-ranking?

There is a common approach to re-rank the search results with a model that takes some additional factors into account. Those models are usually trained on clickstream data of a real application and tend to be very business-specific. Thus, we’ll not cover them right now, as there is a more general approach. We will use so-called cross-encoder models.

Cross-encoder takes a pair of texts and predicts the similarity of them. Unlike embedding models, cross-encoders do not compress text into vector, but uses interactions between individual tokens of both texts. In general, they are more powerful than both BM25 and vector search, but they are also way slower. That makes it feasible to use cross-encoders only for re-ranking of some preselected candidates.

This is how a pseudocode for that strategy look like:

async def search(query: str):

keyword_search = search_keyword(query)

vector_search = search_qdrant(query)

all_results = await asyncio.gather(keyword_search, vector_search) # parallel calls

rescored = cross_encoder_rescore(query, all_results)

return rescored

It is worth mentioning that queries to keyword search and vector search and re-scoring can be done in parallel. Cross-encoder can start scoring results as soon as the fastest search engine returns the results.

Experiments

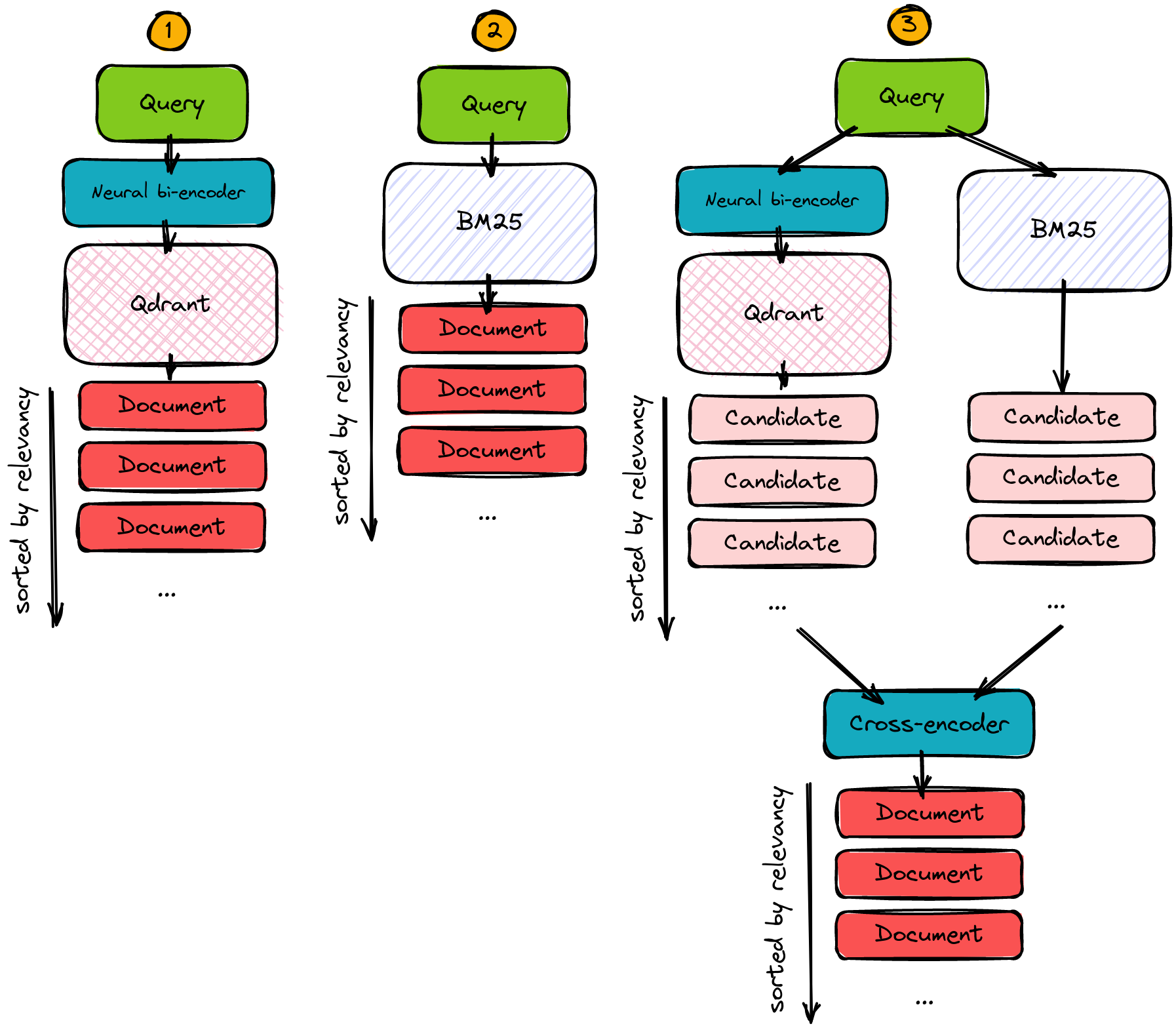

For that benchmark, there have been 3 experiments conducted:

Vector search with Qdrant

All the documents and queries are vectorized with all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model, and compared with cosine similarity.

Keyword-based search with BM25

All the documents are indexed by BM25 and queried with its default configuration.

Vector and keyword-based candidates generation and cross-encoder reranking

Both Qdrant and BM25 provides N candidates each and ms-marco-MiniLM-L-6-v2 cross encoder performs reranking on those candidates only. This is an approach that makes it possible to use the power of semantic and keyword based search together.

Quality metrics

There are various ways of how to measure the performance of search engines, and Recommender Systems: Machine Learning Metrics and Business Metrics is a great introduction to that topic. I selected the following ones:

- NDCG@5, NDCG@10

- DCG@5, DCG@10

- MRR@5, MRR@10

- Precision@5, Precision@10

- Recall@5, Recall@10

Since both systems return a score for each result, we could use DCG and NDCG metrics. However, BM25 scores are not

normalized be default. We performed the normalization to a range [0, 1] by dividing each score by the maximum

score returned for that query.

Datasets

There are various benchmarks for search relevance available. Full-text search has been a strong baseline for most of them. However, there are also cases in which semantic search works better by default. For that article, I’m performing zero shot search, meaning our models didn’t have any prior exposure to the benchmark datasets, so this is effectively an out-of-domain search.

Home Depot

Home Depot dataset consists of real inventory and search queries from Home Depot’s website with a relevancy score from 1 (not relevant) to 3 (highly relevant).

Anna Montoya, RG, Will Cukierski. (2016). Home Depot Product Search Relevance. Kaggle.

https://kaggle.com/competitions/home-depot-product-search-relevance

There are over 124k products with textual descriptions in the dataset and around 74k search queries with the relevancy score assigned. For the purposes of our benchmark, relevancy scores were also normalized.

WANDS

I also selected a relatively new search relevance dataset. WANDS, which stands for Wayfair ANnotation Dataset, is designed to evaluate search engines for e-commerce.

WANDS: Dataset for Product Search Relevance Assessment

Yan Chen, Shujian Liu, Zheng Liu, Weiyi Sun, Linas Baltrunas and Benjamin Schroeder

In a nutshell, the dataset consists of products, queries and human annotated relevancy labels. Each product has various textual attributes, as well as facets. The relevancy is provided as textual labels: “Exact”, “Partial” and “Irrelevant” and authors suggest to convert those to 1, 0.5 and 0.0 respectively. There are 488 queries with a varying number of relevant items each.

The results

Both datasets have been evaluated with the same experiments. The achieved performance is shown in the tables.

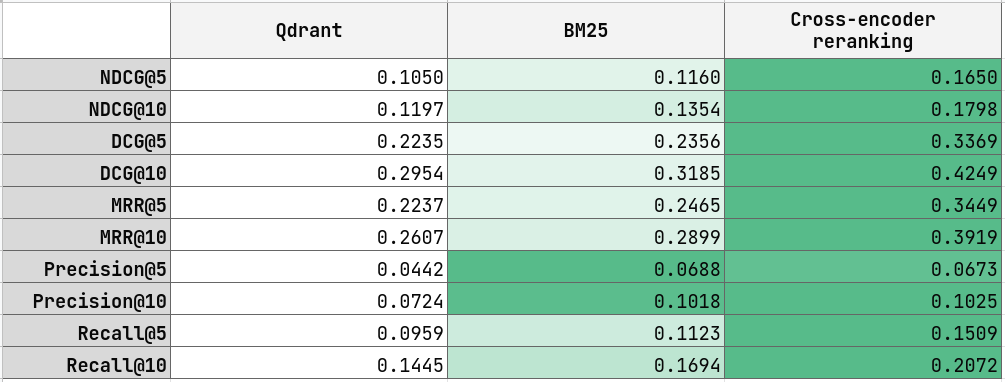

Home Depot

The results achieved with BM25 alone are better than with Qdrant only. However, if we combine both methods into hybrid search with an additional cross encoder as a last step, then that gives great improvement over any baseline method.

With the cross-encoder approach, Qdrant retrieved about 56.05% of the relevant items on average, while BM25 fetched 59.16%. Those numbers don’t sum up to 100%, because some items were returned by both systems.

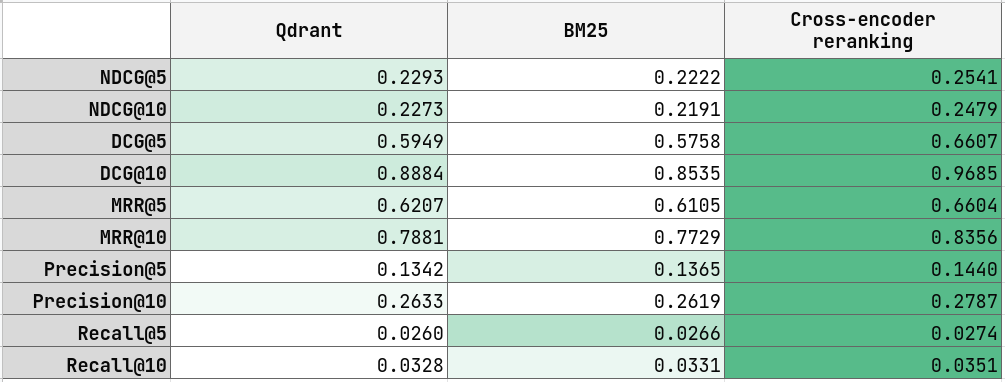

WANDS

The dataset seems to be more suited for semantic search, but the results might be also improved if we decide to use a hybrid search approach with cross encoder model as a final step.

Overall, combining both full-text and semantic search with an additional reranking step seems to be a good idea, as we are able to benefit the advantages of both methods.

Again, it’s worth mentioning that with the 3rd experiment, with cross-encoder reranking, Qdrant returned more than 48.12% of the relevant items and BM25 around 66.66%.

Some anecdotal observations

None of the algorithms works better in all the cases. There might be some specific queries in which keyword-based search will be a winner and the other way around. The table shows some interesting examples we could find in WANDS dataset during the experiments:

| Query | BM25 Search | Vector Search |

|---|---|---|

| cybersport desk | desk ❌ | gaming desk ✅ |

| plates for icecream | "eat" plates on wood wall décor ❌ | alicyn 8.5 '' melamine dessert plate ✅ |

| kitchen table with a thick board | craft kitchen acacia wood cutting board ❌ | industrial solid wood dining table ✅ |

| wooden bedside table | 30 '' bedside table lamp ❌ | portable bedside end table ✅ |

Also examples where keyword-based search did better:

| Query | BM25 Search | Vector Search |

|---|---|---|

| computer chair | vibrant computer task chair ✅ | office chair ❌ |

| 64.2 inch console table | cervantez 64.2 '' console table ✅ | 69.5 '' console table ❌ |

A wrap up

Each search scenario requires a specialized tool to achieve the best results possible. Still, combining multiple tools with minimal overhead is possible to improve the search precision even further. Introducing vector search into an existing search stack doesn’t need to be a revolution but just one small step at a time.

You’ll never cover all the possible queries with a list of synonyms, so a full-text search may not find all the relevant documents. There are also some cases in which your users use different terminology than the one you have in your database. Those problems are easily solvable with neural vector embeddings, and combining both approaches with an additional reranking step is possible. So you don’t need to resign from your well-known full-text search mechanism but extend it with vector search to support the queries you haven’t foreseen.